Nuenen, the Netherlands

|

| The Potato Eaters (1885) by Vincent van Gogh |

As he lays down in bed, Vincent sees a cloaked visitor standing at the door of his studio who, with a hypnotic look, beckons him to follow. He has seen that face before but where and when?

Without thoughts, Vincent follows the visitor into the cold darkness of the Northern sky studded with stars that look like swirling comets overlooking a landscape of saturated colors where trees dances like emerald flames. They walks past a derelict church and toiling peasants into a city with busy streets where Vincent sees Sien and Margot being pushed away from him, his brother Theo ignoring him while feasting with rich clients, and finally at the bank of a river, his two cousins calling out to him to board a steamship ready to depart for the Dutch East Indies.

When Vincent looks at him again, the cloaked visitor has morphed into a naked androgynous figure pulling him onto Fokke's ghostly Flying Dutchman filled coffee beans which, as he looks closer, swell into severed human heads. As he turns around in disgust, the visitor has taken the form of Matatuli, the author of Max Havelaar, laughing at him …

| Water Sprite (1882) by Earnst Josephson. It was a sketch of this painting that Theo mentioned to Vincent in the letter. |

Vincent wakes up… shaken by the strange dream with the face of the stranger still lingering in his memory – infinitely good and tender but also sad and melancholy, as though he had seen all the evils in the world… Indeed, he has. It was the face of Dante painted by Giotto. As it is said, the first thing Giotto puts in the facial expressions is goodness.

In a letter Vincent received the day before, his brother Theo, an art dealer in Paris, wrote about a sketch by a Swedish painter with a prominent “Dantean figure -- the symbol of an evil spirit that lures people into the abyss.” And it crept into his dream, despite – or because of – its perplexing description.

Surely the two cannot be reconciled, Vincent thinks. A sober, austere Dante, who returned from Hell was entirely filled with indignation and protest at what he saw in the Inferno. He cannot be the same as a Mephistopheles who lures unsuspecting people into eternal condemnation with a promise of sweet rich rewards. We can’t have a Dantean figure play a satanic role without a huge misconception of character, can we?

Was the dream an agonized warning against or a sweet invitation to Hell? The answer entirely depends on the identity of the visitor, but what if Mephistopheles’ finest trick is to impersonate Dante convincing the world that Satan is already facing his punishment in the Center of Hell? Would there be a way to see through his trick – a moral yardstick that can always tell right from wrong?

|

| Man breaking up the soil (1883) by Vincent van Gogh |

For months, Vincent has been grappling with the question. To him, there is one thing that stands above all: love for humanity. Just as in Les Misérables, a student sings of his love for his mother — the Republic — at the time of the Revolution of ’30,

“If Caesar had given me

Glory and war,

And if I was forced to forgo

My mother’s love,

To great Caesar would I say,

Take back your scepter and your chariot,

I love my mother more, hey!,

I love my mother more.”

With his art, Vincent hopes to sing his “love for mother” — that is, love of mankind. The old foundation of universal brotherhood that has been tested and found good for so many centuries is enough for him. Isn’t love of one’s fellow man something to take for granted in everyone as the basis of just about everything? He’s like to think so, but some people, however, believe there are better foundations.

Vincent remembers, when as a volunteer lay pastor among poor miners of Wasmes, he threw himself to his duties and was faithful in helping and comforting those people who worked in very dangerous mines where many die, whether going down or coming up, or by suffocation or gas exploding, or because of water in the ground, or because of old passageways caving in and so on. The great danger was tragically shown when many people lost their lives in the collapse of the L’Agrappe coal mine at Frameries, just east of Wasmes.

|

| Miners' wives carrying sacks of coal (1882) by Vincent van Gogh |

Wasmes was a somber place, and at first sight everything around it had something dismal and deathly about it. The workers there were usually people, emaciated and pale owing to fever, who looked exhausted and haggard, weather-beaten and prematurely old, the women generally sallow and withered. All around the mine were poor miners’ dwellings with a couple of dead trees, completely black from the smoke, and thorn-hedges, dung-heaps and rubbish dumps, mountains of unusable coal.

Vincent once took in a very sick patient, burned from head to foot by an explosion in the mine. He sat up with him and helped to bandage his wounds for months while his patient slowly recovered. Then the church authorities dismissed him for "undermining the dignity of the priesthood” after they found him sleeping on straw in a small hut having given up his comfortable lodgings at a bakery to a homeless person.

The dignity and respectability of institution must be rooted in its love of mankind, Vincent believes. He no longer counts himself a friend of present-day Christianity, even though he believes the founder was sublime. He has seen through present-day Christianity only too well. Then, again, he has had his revenge since then. How? By worshiping the love that they — those at the theological school — call sin, by respecting a whore etc., and not many would-be respectable, religious ladies…

|

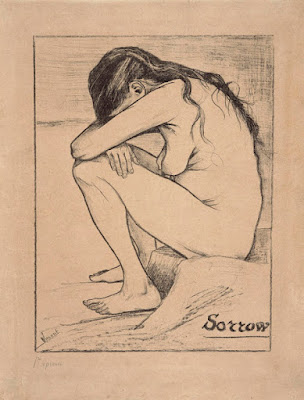

| Sorrow (1882) by Vincent van Gogh |

Vincent has made peace with himself over the fallout with the Church. But family is a different thing. That’s why the heated quarrel with Theo has been traumatizing him since August.

Vincent thinks, the issue here is that if he and Margot choose to love each other, be attached to each other — indeed have been for a long time — this is no wrongdoing on their part nor something for which people may blame either him or her. And in his view it’s absurd that people felt they should get worked up about her being twelve years older – supposedly in his or her “interest”.

Vincent couldn’t care less that after he proposed a marriage to Margot, people started to gossip or stopped visiting his father, the village minister, because they don’t want to meet him. Equally troubling for him is how they browbeat his “bad behaviors”, that is, associating with “dirty and drunk peasants” who model for his sketches and even living like them.

“Why not paint something more cheerful, more respectable? People don’t want to buy at the poor and the suffering.” Theo can go on and train himself well in that system of prudence and respectability and suchlike, then he will go far, precisely in mediocrity. To Vincent, the life we are in is such a mystery that the system of ‘Respectability’ is certainly too narrow — so, for him, that has lost its credit.

|

| Avenue of poplars in autumn (1884) by Vincent van Gogh |

Now it’s dismal outdoors — the fields a marble of clods of black earth and some snow, usually a few days of fog and mud in between — the red sun in the evening and in the morning — crows, shriveled grass and withered, rotting vegetation, black bushes, and the branches of the poplars and willows vicious as wire against the dismal sky. It’s quite in harmony with the interiors, very gloomy in these dark winter days, and with the physiognomies of peasants and weavers from whom one doesn’t hear complaints, although they have a hard time of it.

A weaver who works hard makes a piece of 60 ells, say, in a week. While he weaves, a woman has to spool for him; that is winding yarn on to the bobbins — so there are two who are working and have to live on it. On that piece he makes a net profit of, say, 4.50 guilders in that week — and nowadays when he takes it to the manufacturer he’s often told that he can only bring a new piece in a week or a fortnight’s time.

|

| Weaver (1884) by Vincent van Gogh |

So not only wages low, but work fairly scarce. There’s consequently often something harried and restless in these people.

It’s a different mood from that of the miners he lived with in a year of strikes and many accidents.4 That was even worse — but all the same, it’s often heart-rending here too — the people are quiet, and literally nowhere have I heard anything resembling inflammatory arguments, even though they look as little cheerful as the cab-horses or the sheep that are transported by steamer to England.

‘I would never do away with suffering, for it is often that which makes artists express themselves most vigorously’, Millet once said. Sensier even said of Millet: A peasant dedicated to hard work on the land, he constantly had in his heart compassion and pity for the rural poor. He was neither a socialist nor an ideologue, and yet, like all profound thinkers who love humanity, he suffered at the sufferings of others, and he needed to express them. To do that, he had only to paint the real peasant at work.

For his part, Vincent regards and respects the genuinely human, living with nature — not going against nature — as refinement. “The most touching things the great masters have painted still originate in life and reality itself.” Vincent thinks, “Painting peasant life is a serious thing, and I for one would blame myself if I didn’t try to make paintings such that they give people who think seriously about art and about life serious things to think about. He will paint them the same way that Breton writes about them in his poem “Return from the fields (To François Millet)”

|

| The Gleaners (1857) by Jean-François Millet |

’Tis that uncertain hour in which the evening star,

Still pale against the pale night sky,

Appears, twinkles, slips behind a veil,

Tiring the watcher’s searching gaze.

’Twixt wheat and vetch,

With dusty thistles lined,

The tawny path still can be descried

Among the fertile fields.

From high above, ineffable,

Amethyst-colored light caresses it

And the artist, for want of other word,

Can only call it purple.

Across the flat or gently sloping mead,

Losing their furrows, finding them again,

It winds among the grass, where sounds

The cricket’s shrill and reedy song.

By banks gilded by eventide it goes

Under the clear air

Through which is heard the church bell’s sonorous note,

Tolling in silent village streets.

|

| The Potato Planters (ca. 1861) by Jean-François Millet |

The peasant twice browned

By the twilight and suntan,

Forehead bathed in the pale light,

Makes his way home, his labour done.

Bearing on his shoulder scythe or spade,

Slowly he goes,

Moistening his dry chest

With mist, and with the scent of wheat.

Slowly he goes, at his unhurried pace,

With calm and heavy tread;

The west, like a furnace smoldering,

Turns him a deep and fiery bronze.

Beneath his cottage’s black roof,

Where rises a faint blue strand of smoke,

There glows a spot of red;

The soup is singing on the fire.

His partner’s strong and firm,

The children thrive,

Old age approaches – what is its sting,

Set beside childhood’s gay springtime?

Thus he plods from habit long ingrained,

Thus will he plod until his dying day;

Content if through his humble toil

The wheat is heavy and the barley fair.

|

| The Song of the lark (1884) by Jules Breton |

When Vincent worked as an art dealer in London in 1873, he was shocked by the poverty on the streets of London. But social reform was gaining traction. Publications like John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty and George Eliot’s Middlemarch deeply influenced his idea of art.

For Vincent, there’s a cardinal point of distinction between before and after the revolution — the reversal of the social position of the woman, and the collaboration one wants between men and women with equal rights, with equal freedom. To his mind conventional morality is all back-to-front and he hopes it will be turned around and replaced in time.

This old society is going under through its own fault — there’s a new society that has come into being and grown, and will go on. There is what emanates from revolutionary and what emanates from anti-revolutionary principles. The minds that can’t agree are real. The mill is there no longer, but the wind’s still there.The barricade may no longer be visible in the form of paving-stones like in 1848, but still definitely exists and persists in society as regards the irreconcilability of old and new.

|

| Daumier’s The Revolution of 1848. A family on the barricades |

Vincent had always believed that he and Theo were like the two brothers in Daumier’s The Revolution of 1848. A family on the barricades who were on the same side and both fell, one a day after the other, for the same cause. So among all the troubles that he is going through, the most distressing thing for him was to find that the barricade actually stands between him and his brother, Theo in front of it as a soldier of the government, himself behind it as a revolutionary or rebel.

Vincent knows that his duty compels him to love my father, my brother — and he does — but we live in an age of innovation and reform, and many things have changed utterly, and in consequence of this he sees, he feels, he believes differently from his father and from Theo.

In the past Vincent may have been very passive and very gentle and quiet, but he has made up his mind that was enough. If one wants to be active, one mustn’t be afraid to do something wrong sometimes, not afraid to lapse into some mistakes. To be good — many people think that they’ll achieve it by offending no one — and that’s a lie. That leads to stagnation, to mediocrity. And for his part, Vincent has no intention of being bored.

He says to himself, “Do a great deal or die.”

By the end of that winter, Vincent would have made many sketches which led to a major breakthrough “The Potato Eaters” (1885). Two years later at the height of his creative career, he would say, “What I think about my own work is that the painting of the peasants eating potatoes that I did in Nuenen is after all the best thing I did.”

|

| Peasant burning weed (1883) by Vincent van Gogh |

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Note: Apart from the imagined dream sequence in the beginning, almost all of the content are from http://vangoghletters.org which contains all of the artist's works and letters.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment!